Power and "new media" on the threshold of the early modern period

Throughout his reign, Emperor Maximilian I commissioned important scholars and artists to capture his deeds and foundations in words and pictures. His memory, his ‘Gedechtnus’, was to be preserved for posterity and be an example to future monarchs. He made use of new techniques and strategies that were developed on the threshold of the early modern era.

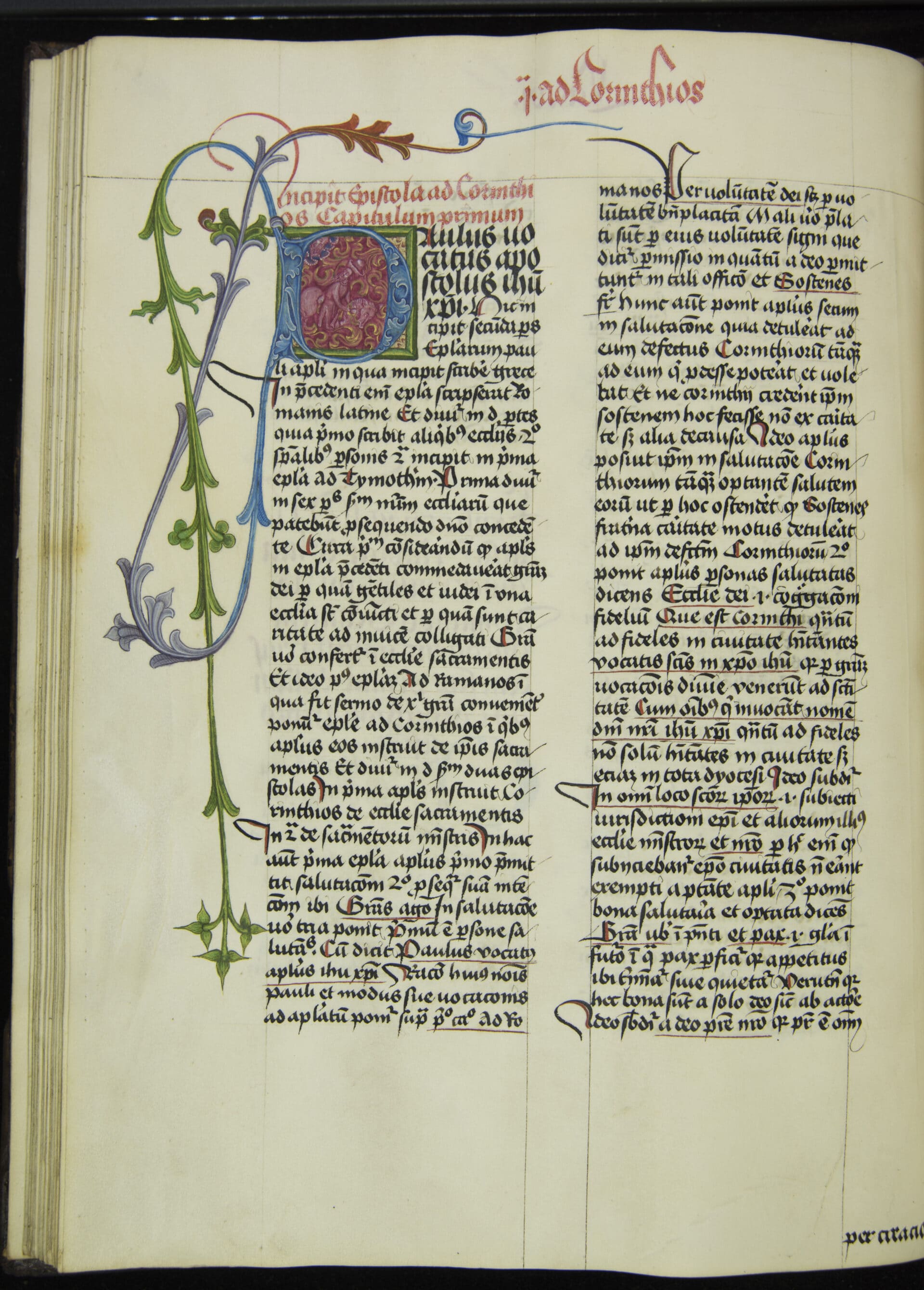

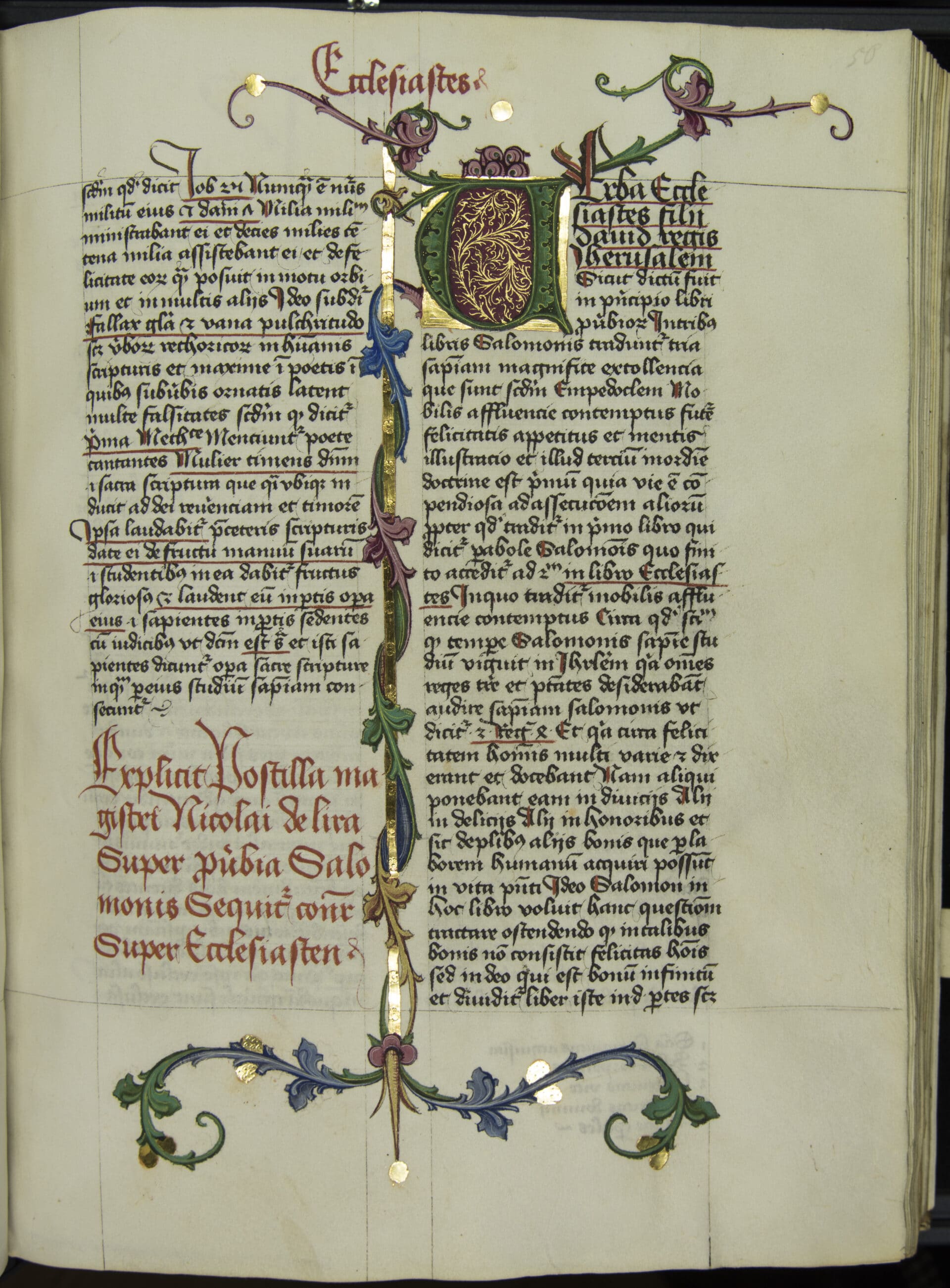

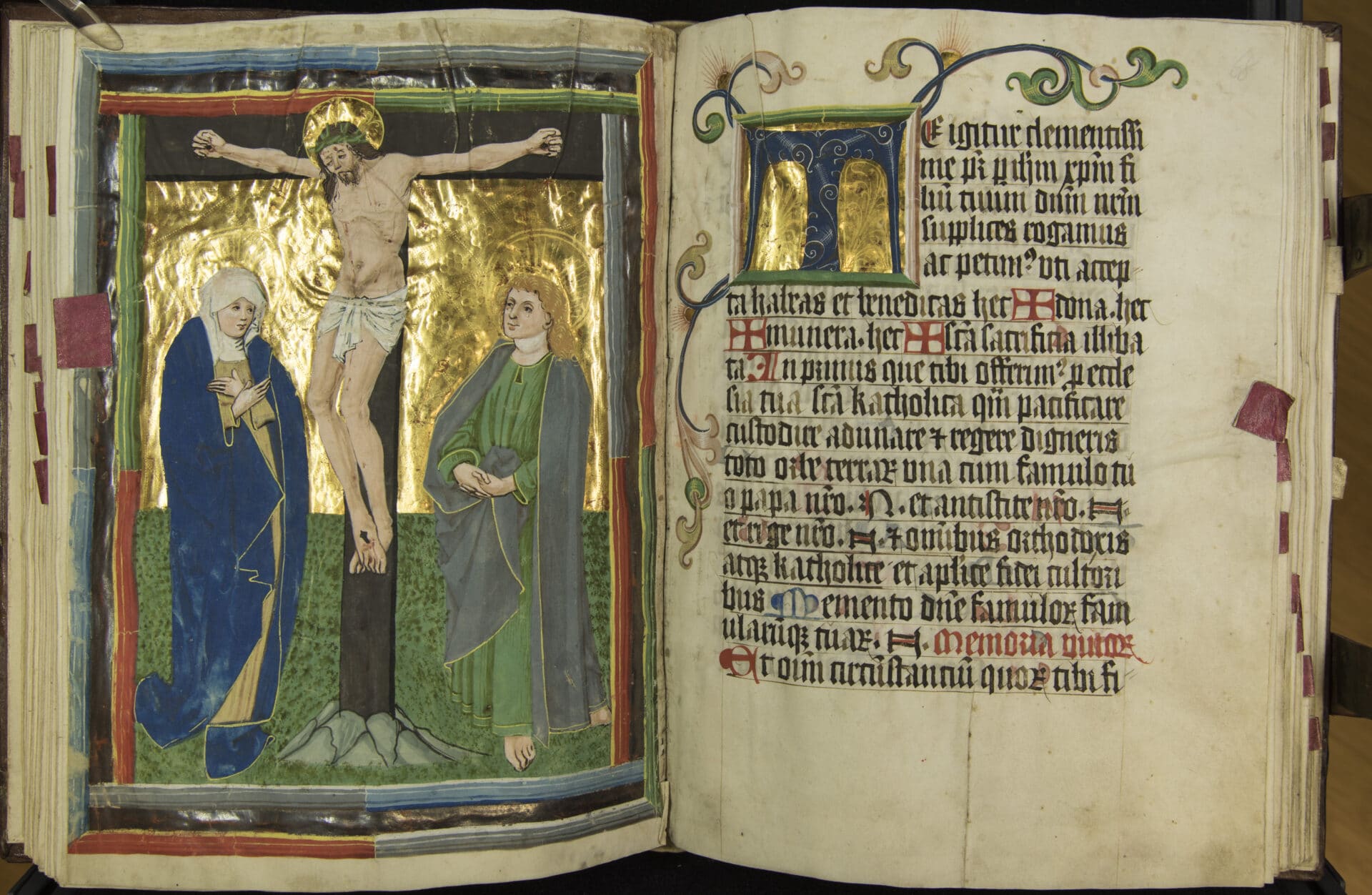

The production of manuscripts had experienced a commercialisation in the late Middle Ages; Workshops such as those of Ulrich Schreier in Salzburg and Vienna supplemented the monastic writing rooms and also allowed private individuals to have manuscripts made to their taste. Around 1450, the invention of printing by Johannes Gutenberg ushered in a period of media change and created the basis for the mass production of texts. The first printed books were designed on the model of medieval manuscripts. Maximilian made use of the new media and had biographical works made that celebrated his achievements in narrative form. Maximilian skilfully had historical facts embedded in a fictional form: As knight Theuerdank, he embarks on countless adventures on his way to his bride Ehrenreich, who stands for his first wife, Mary of Burgundy (1457–1482), and as the White King he takes care of his ‘Gedechtnus’.

Freydal is an illustrated prose narrative on jousting tournaments that tells the life story of young Emperor Maximilian I in an allegorical way. As handwritten notes show, Maximilian himself repeatedly intervened in the creation of the works to correct them. He was not only interested in having them reproduced, but also in perfecting them: For Theuerdank, whose first edition appeared in 1517, a separate font was designed, each with several variants of individual letters and many decorative elements. In addition, the work contains numerous woodcuts made by prominent artists of the time. Since the ability to read was the exception rather than the rule, Maximilian I also spread his messages by other means: Ordinances were read out publicly and pictures were "fed to the public" through coins. During his lifetime, Maximilian was more than occupied with his own death and posthumous reputation: The planning of his burial sites that took many years, or his commissioning of a portrait of him to be painted after his death testifies to this. In addition, leaflets with motets, i.e. songs, have been preserved, which were made to spread the news of Maximilian's death immediately after he passed away in 1519.

Wann ain Mensch stirbt, So volgen Ime nichts nach dann seine werkh […] (When someone dies, nothing follows him except his works [...]) Wer ime in seinem leben kein gedächtnis macht, der hat nach seinem todt kein gedächtnus und desselben Menschen wirdt mit den glockendon vergessen. (Those who do not make things to be remembered by while they are alive will not be remembered after their death and will be forgotten with the sound of a bell.) From ‘The White King’

From the "Weißkunig"